Inflation pressure: Energy is the main push

Global oil prices, though retreating modestly from their peak in March, remain elevated, while natural gas prices continue to creep up. So the energy is the main push for inflation.

A domestic petroleum supply shortage has exacerbated Vietnam’s energy crunch.

Inflation remains the dominant buzzword in economic headlines. Unlike many other parts of the world, Asia has seen benign inflation for the past year, but this is changing rapidly. In ASEAN, there have been notable upside risks to inflation since the start of 2022, pushing both core and headline inflation much higher than their pre-pandemic levels.

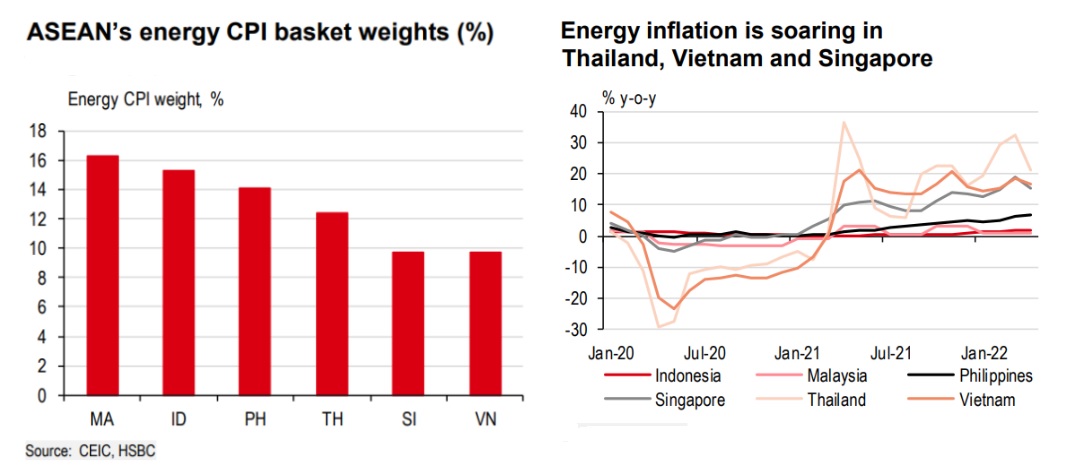

That said, the impact is uneven across countries, with inflation pressures in Singapore, Thailand and the Philippines particularly acute but still relatively contained in Vietnam, Malaysia and Indonesia. However, headline inflation is likely to soon rise sharply even for the latter groups of countries, not least given elevated energy prices.

This is not good news for ASEAN. After all, with the exception of Malaysia and Indonesia (for natural gas and coal), economies are large net energy importers. The Philippines and Thailand are particularly sensitive to soaring energy prices, evidently shown in their latest CPI readings. Higher oil prices have pushed their headline inflation above their central banks’ respective target by a wide margin. Malaysia and Indonesia also have higher shares of energy-related components in their CPI baskets, such as transport costs. But the extent of energy pass-through varies, depending on local price adjustments and/or the level of taxation on fuel. So far, Thailand faces the most severe rise in energy prices, up 20% y-o-y.

In Indonesia, energy inflation has been rising steadily since the start of 2022, reaching 4% y-oy in April. The government has pledged to provide USD10.8bn from the budget, originally slated for social protection, to safeguard locals from rising commodity prices. Meanwhile, the 1ppt VAT hike in April will likely add to price pressures (by HSBC’s estimates it could contribute 0.4ppt to core CPI inflation through year-end).

However, HSBC said the surge in export revenues from coal and other commodities raises the room for Indonesia to extend fuel subsidies. Recently, the Indonesian parliament approved the government’s request to raise 2022 energy subsidies and compensation by IDR349.9trn (USD23.8bn). Out of this, IDR74.9trn has been directed for energy subsidies, while IDR275trn is slated for additional compensation for state energy firms Pertamina and PLN. Despite additional subsidies, the windfall gains from high commodity prices and other budget revisions will likely result in a narrower fiscal deficit of 4.5%.

Energy price inflation has so far also been more contained in Malaysia, thanks to favourable base effects, and price controls. In 2022, the government expects to spend MYR28bn (USD6.7bn) on fuel subsidies alone, more than double that of last year. As the only net exporter of oil and gas in ASEAN, the revenues generated from exports make energy subsidies fiscally more sustainable, although better targeting would help to free up funds for more investment in other areas and help mitigate the environmental impact of excessive fuel consumption.

However, this is not the case for commodity importers. With the exception of Singapore, the magnitude of fiscal assistance to curb inflation is constrained by the lack of fiscal room. Thailand, in particular, is exposed to higher oil prices. For quite a while, transport costs are the main culprit of high prices, pushing inflation to a 13-year-high in March. And the pressures continue to build: initially, the government had capped the price of diesel at THB30/litre, thanks to the help from the Fuel Oil Fund.

However, it was forced to raise the cap to THB32/litre from 1 May, and further to THB33/litre from 31 May, as the Fuel Oil Fund is severely depleted. The government therefore announced some targeted relief measures to alleviate living cost pressures for households, which will be rolled out over the coming months: including cash assistance for cooking gas for poor householders, lower electricity charges and a further cut of THB5/litre in the excise tax on diesel. The Transport Ministry also proposed a comprehensive fuel package across all transport sectors, hoping to offset some high energy prices.

In the Philippines, the CPI for electricity, gas, and other fuels has been rising by double digits y-o-y since August 2021, with inflation hitting 20% in April. To help citizens cope, the Duterte government provided PHP6,500 (USD120) in fuel subsidies to each public utility vehicle driver, while implementing a fuel subsidy programme for 159,000 farmers and fishermen. The Department of Energy has also been in close coordination with private oil companies to secure discounts for the public transport sector ranging from PHP1 to PH4/litre of gasoline.

Moreover, the incoming President, Ferdinand Marcos Jr., is seeking to scrap the 12% VAT on power rates once he steps in office. However, given the narrow fiscal space due to the pandemic, this proposal will likely meet resistance from the President’s future economic advisors.

In Vietnam, energy price inflation has also been persistent. Transport prices rose to record highs, replacing food inflation to be the main driver for Vietnam’s headline inflation. On top of surging global oil prices, a domestic petroleum supply shortage has exacerbated Vietnam’s energy crunch. Since January, Vietnam’s largest refiner, Nghi Son Refinery, has been running at a reduced operating rate, coming close to a shutdown in February, before improving to about 80% capacity in March. This has forced the authorities to look for alternatives to alleviate the energy pressure.

The government has pledged to import an additional 2.4m cubic metres of petroleum in 2Q22, which is already reflected in Vietnam’s rising imports data. Meanwhile, since 1 April, the government has also cut the environment tax, the largest of all taxes and fees on fuel, to VND2,000 on gasoline and VND700-1,000 on other fuels. Despite elevated energy prices, moderate food inflation, which has a bigger weighting in the CPI basket, has so far helped to curb the overall rise in headline inflation.

Unlike regional peers, Singapore’s rising price pressures have been broad-based. That is partly because of greater wage and labour market pressures, which in turn reflect the fact that Singapore was able to administer more generous fiscal support over the course of the pandemic. In fact, there are signs that high wage growth has been passed onto inflation since 4Q21. Coupled with demand-led inflation, high energy prices are also pushing up core prices. Unlike many central banks that monitor a core CPI measure excluding food and energy prices, the MAS’ core CPI includes electricity and gas utilities, reflecting oil price changes in a lagged manner.

Therefore, soaring energy prices since the start of 2022 suggest that electricity tariffs will likely put persistent upward pressure on core in 2Q-3Q22. That said, Singapore is in a much better fiscal position to help lower living costs. Despite shifting its focus to long-term priorities, the FY2022 budget in February included additional short-term assistance to households worth SGD560m. This comes in the form of various vouchers, including consumption vouchers and utility subsidies. If needed, Singapore stands ready to roll out additional measures to combat inflation.