Looking back to the US tariffs

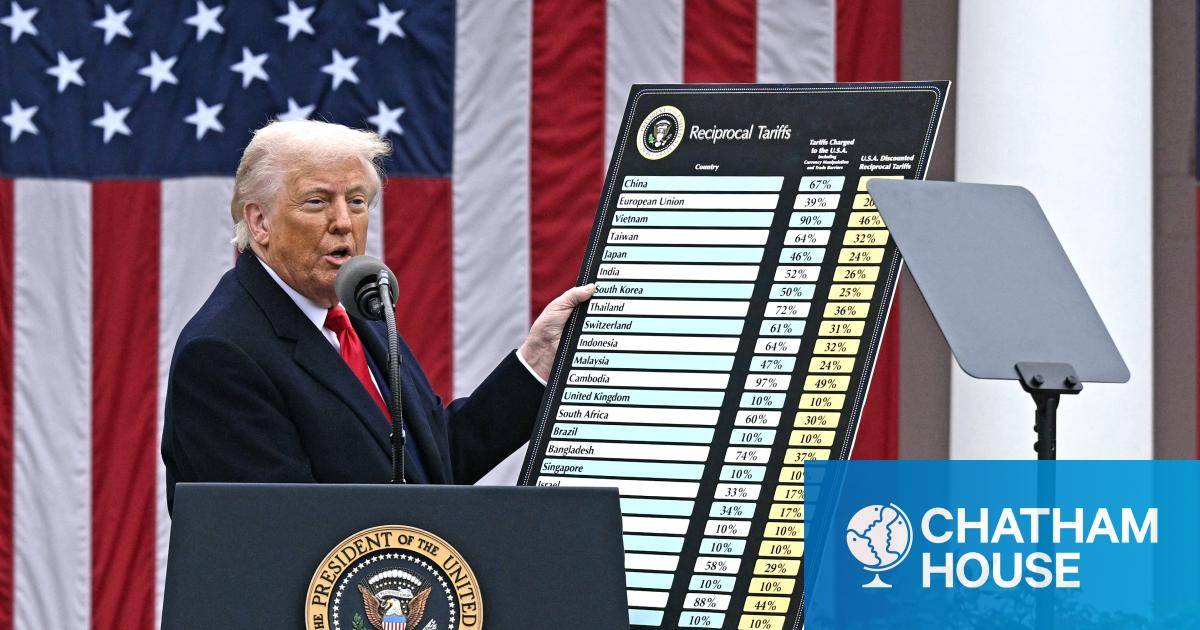

It was just over a year ago that newly-election President Trump started to put some numbers on the sort of tariffs he was going to implement. The world was in shock and markets started reeling; particularly in the wake of the ‘liberation day' tariff rate reveal on April 2nd.

It was just over a year ago that US President Trump started to put some numbers on the sort of tariffs he was going to implement.

But a year on, and tariffs have been the dog that didn't bite. Growth has not collapsed in the US or elsewhere, US inflation has not surged as many feared, and financial markets have not just settled down from the April tumult but have flourished both inside and outside the US. Add to all this the bonus of hefty tariff revenues for the US Treasury, and we might ask the question, what's not to like about tariffs?

The difficulty in making an optimistic conclusion about tariffs, at least relative to the dire predictions made beforehand, is that there's no counterfactual. Yes, global growth has held up, US inflation has not surged, extensive disinflation has not been experienced elsewhere, and financial markets, particularly stocks, have boomed.

However, we don't know what would have happened if tariffs had never been announced. Perhaps growth would have been much stronger, US inflation more becalmed, and financial assets even stronger. While it is reasonable to ask these questions, Steven Barrow, Head of Standard Bank G10 Strategy, said the adverse economic and financial market fallout from tariffs has been smaller than anybody expected and might not have cost the global economy and asset prices very much at all, relative to a world where tariffs had never existed. If it is the case that tariffs have cost very little, the obvious question is, why?

We can only guess at the answers. One is that the effective tariff rate in the US, while above 10%, is still a good deal lower than initial estimates around Liberation Day, as the US has hammered out trade deals with many countries.

Another is that some countries have been able to find a way around tariffs. For instance, only around 30-40% of firms in Mexico and Canada were claiming USMCA tariff exemption at the start of 2025; that's now risen to around 90%.

A third factor is that countries outside the US have used policy room to ease fiscal and/or monetary policy. And lastly, we'd note that China, which has been, by far, the hardest hit by tariffs, has somehow managed to redirect itself to seemingly shrug off the tariff effect. The sum total of all this is, as BoJ member Masu said last week, that the economic impact of tariffs has abated and there is now virtually no impact on the economy at all.

In addition to the fact the negativity around tariffs has been disproved by events, the US is raking in extra tariff revenue that's north of USD20bn per month, a near 200% rise on revenues in 2024. Again, we can ask, what's not to like about tariffs? If there's nothing to fear in tariffs, at least relative to pre-tariff predictions, then what might it mean going forward?

One implication is that the market might not fret about the ruling by the Supreme Court on tariffs, which should come soon. Another is that financial markets may not be too worried if new tariffs are added, and not just because Trump has a habit of rescinding or reducing the tariffs. Throwing these things into the mix might really mean that the US—and the rest of the world – has got off scot-free in spite of the fact that US tariffs have been increased to their highest level since the early 1940s. But, as you might have guessed already, this is not necessarily the right conclusion, at least when it comes to the US.

For Steven Barrow’s view is that the ‘cost' of tariffs has been more in the reputational damage done to the US than their harmful economic effects on others. For if we look at the tariffs in conjunction with other policies, such as those on migration, Fed independence and more, it seems that reputational harm has occurred and has had a cost. US Treasury yields have not come down despite significant Fed easing, and the US dollar has fallen. And note that the theory on tariffs is that they should lift the dollar, not lower it.

“We see the fall as a result of the adverse reputational effect of tariffs and the other policies we mentioned. The irony, of course, is that if the ‘cost’ of tariffs is a lower US dollar, it might actually be a cost that the President wanted all along”, said Steven Barrow.