Sterling could perform better

The sterling might do better if the TFP performs well in the upcoming years.

The pound has risen by close to 6% since the depths of the Truss debacle in September.

>> Sterling: a good bounce-back trade?

Sterling might have recovered from the mauling it received in September and October when former UK Prime Minister Liz Truss had her very brief spell in charge, but it is still very low in historical terms, and it is hard to see this turning around unless, that is, you are optimistic about what Brexit will mean for the UK economy.

The pound has risen by close to 6% since the depths of the Truss debacle in September. That’s the good news. The bad news is that the pound’s trade-weighted index is still only 7.5% above the lowest levels we’ve ever seen on the BIS’s narrow exchange rate index.

The pound is definitely not out of the woods. It is true that periods of turmoil such as the Tress premiership, the Brexit vote in 2016, or the withdrawal from the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) in 1992, have hit the pound hard, but, even when there is not a crisis, the pound seems to have floundered. And it is not as if this just describes the last few decades; it goes right back to before the advent of floating exchange rates in the 1970s.

Is there a single reason for this, and, if there is, what does it say about the pound’s outlook right now? Mr. Steve Barrow, Head of Standard Bank G10 Strategy, said the answer would be that there’s probably no single reason but, in broad terms, we’d argue that its demise in the pre-float era was largely down to the UK’s diminished global position, including the decline of the pound as a reserve currency, invoice currency for trade, and more.

In recent decades, it’s arguably been harder to hide behind this excuse. More likely is that the UK economy has just performed poorly. But how should we judge this performance? Economic growth data is not good enough in Mr. Steve Barrow’s view, even though it’s commonly cited by those trying to make international comparisons. Instead, measures of productivity, and particularly total factor productivity (TFP), are the best guides to real differences in economic performance.

"TFP measures the extra output that can be gained without increasing the number of inputs. A new research paper on the determination of currencies makes the interesting claim that it is actually expectations about future TFP that are important for currency determination and not actual levels. "What's more, the paper suggests that quite a large amount of variation in exchange rates can be explained by expectations about TFP", said Mr. Steve Barrow.

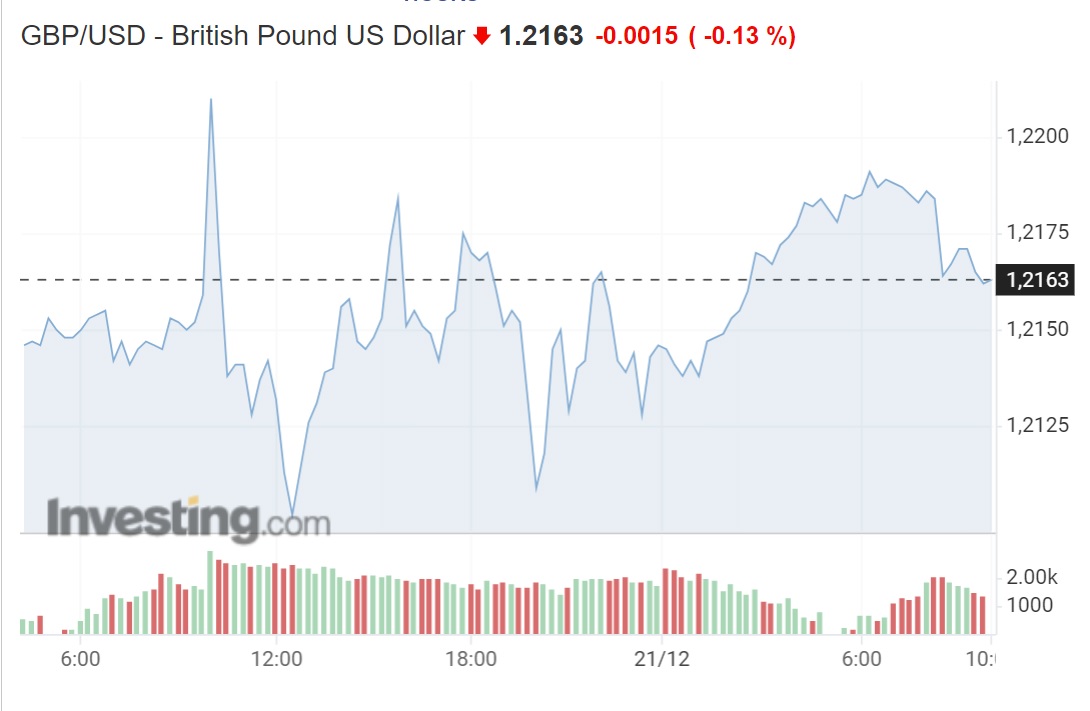

GBP's fluctuations

The unfortunate thing about this, if it is correct, is that it would seem to suggest that the pound will remain under pressure. As far as we can tell, the UK's TFP performance is not only poor, but it is deteriorating in comparison to peers.European Commission forecasts suggest that UK TFP will likely slide over the next couple of years but improve in places such as the US, euro zone, and Japan.

However, much here could depend on whether the UK starts to see some sort of dividend from Brexit. The government has worked tirelessly to try to suggest that there is some sort of benefit to Brexit, although the evidence has been pretty illusive so far. Recent proposals to ease capital rules with respect to banks are just one example of how the government is trying to inject more post-Brexit dynamism into the economy and create the sort of environment that will allow TFP to rebound. Cynics will argue that many of the changes the government is making could have been done inside the EU anyway.

Nonetheless, in Mr. Steve Barrow’s view, it is not quite so clear that coming years will see the same TFP underperformance that we’ve seen in the past, and, if that’s the case, sterling could perform better as a result. At this stage, though, the jury is out, and we suspect that most investors will continue to see the UK as a TFP laggard and price the pound accordingly", said Mr. Steve Barrow.