Two headwinds for the FED

The US seems unlikely to escape a recession as it pays for excessive Covid-related fiscal stimulus, and a Fed that fell far behind the curve. The “price” of these failures will likely be a stronger dollar.

The FED’s forecasts suggest that members feel the fed funds target rate will have to rise to over 4.5% and hold there throughout 2023 before falling thereafter.

>> The two main alternatives for FED

By most conventional measures, the US is already in recession given the two quarters of negative growth seen in the first half of this year. But the US does not define recessions in this way. The National Bureau of Economic Research’s business cycle dating committee is the adjudicator and may be reticent to call a recession right now while the unemployment rate is so low.

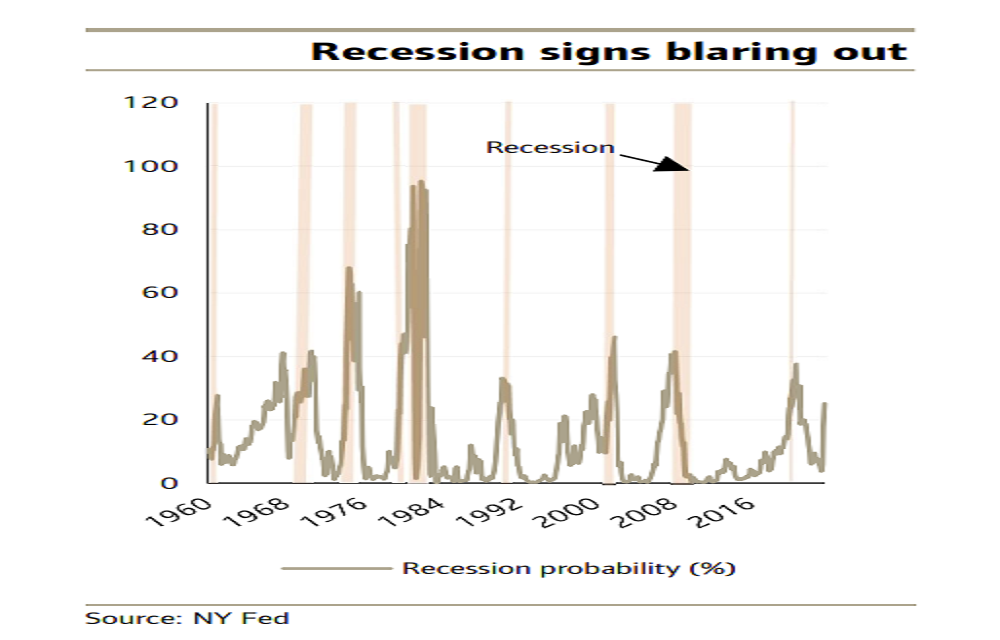

In time, however, the case for calling this a recession is likely to grow. Recession indicators, such as the yield curve, are flashing warning signals. The NY Fed’s recession probability measure generated by the shape of the yield curve and, every time, bar two, that this probability has risen to above one-infour the economy has gone into recession. It is one-in-four right now.

Of course, there are question marks over the reliability of the yield curve as a recession predictor, not least now that market pricing is distorted by the USD5.5tr-plus of treasuries that the Fed has bought under quantitative easing. But Mr. Jeremy Stevens, Asia Economist at the Standard Bank, said that it will be reliable – and the Standard Bank’s forecast of no growth in 2023 is testament to this assumption.

A recession, or even a significant slowdown in growth, should reduce inflationary pressures – but there are at least two headwinds the Fed faces here.

The first is the pandemic-related fiscal support from the government which has left household balance sheets in reasonable shape despite the surge in mortgage costs and the destruction of wealth caused by asset price weakness.

>> When FED will pause rate hikes?

The second headwind is the tightness of the labour market. Job vacancies are now starting to fall fast but, at around 1.7 vacancies for every unemployed person, the Fed’s forecast that a fall in inflation to the target requires a one percentage point rise in the unemployment rate, could be in danger simply because unemployment does not rise fast enough. With household finances and labour markets not cutting the Fed much slack, there’s the danger that the Fed will be forced to “over-tighten”, with big costs for interest-sensitive sectors of the economy.

Right now, the FED’s forecasts suggest that members feel the fed funds target rate will have to rise quickly to just over 4.5% and hold there throughout 2023 before falling thereafter. “Our forecasts are close to this scenario, with the Fed having caught up to what we’ve been suggesting for some time. It is also close to market pricing. However, we should not be cautious about the idea of stability in policy rates through next year. Periods of relatively low and stable inflation have seen tightening cycles end in this way. But periods of rapid inflation and recession, as we saw in the 1970s and 1980s, tend to see a much more volatile end-game, with rates often being hiked again after a pause or slashed very quickly as the economy nose-dives. We can’t say which is more likely now– but we err to the latter scenario even if a sharp reduction in rates is more likely in 2024 than 2023”, said Mr. Jeremy Stevens.

Through all of this economic stress, the US dollar has powered ahead. Indeed, it is precisely because much of the developed world is in a stagflationary hole that the US dollar has been soaring. Conventional wisdom is that sharp rate hikes from the Fed widen rate differentials and lift the US dollar.

This may be part of the story, but we saw the Fed hike rates between 2015 and 2018, with virtually no other central bank following suit, and yet the dollar flatlined. The difference back then was that asset prices, meaning stocks and bonds, were quite strong; today they are very weak. There has been huge asset destruction and, with short-term dollar borrowing, particularly through FX swaps the predominant financing route for such investments, investors have basically become too short of dollars as asset prices have plunged, and they have been forced to buy back dollars to avoid over- hedging their asset positions.

“The above fact implies that the key to a turnaround in the US dollar is not economic recovery and/or an end to Fed tightening but, instead, a recovery in asset prices. We don’t think this is on the cards for some 3-6 months yet, which hints at further dollar strength before any reversal can kick in”, said Mr. Jeremy Stevens.