What to learn from the USD-commodity pricing relationship?

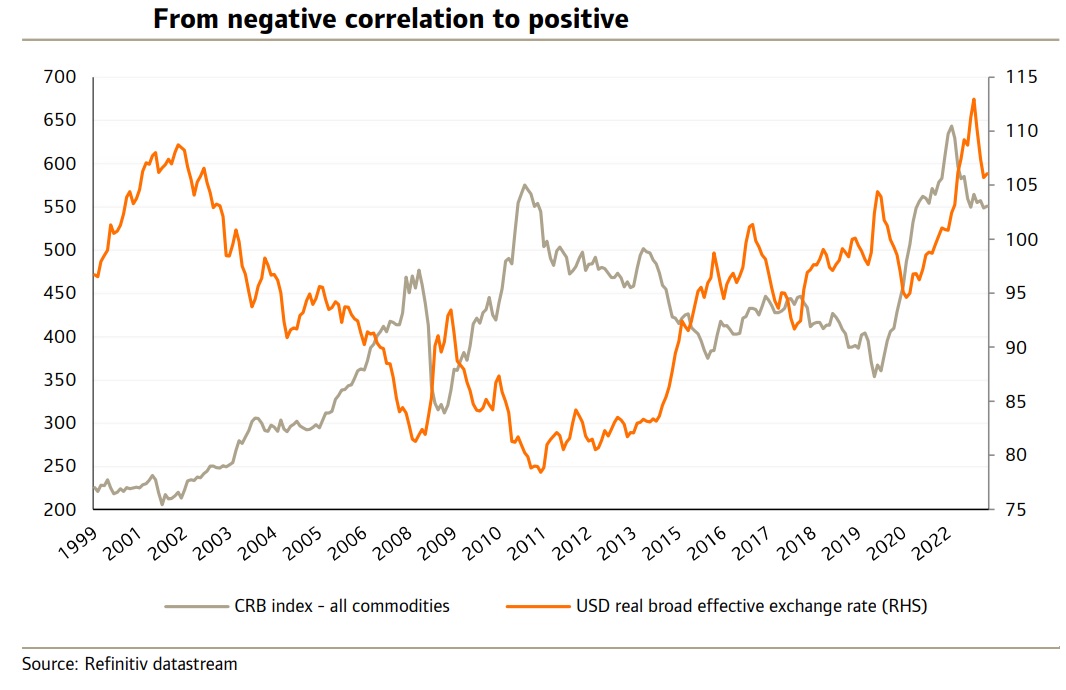

It is noticeable that the correlation between the dollar and commodity prices has flipped in recent years.

The correlation between the dollar and commodity prices has flipped in recent years.

>> How will the US dollar move if the FED pauses rate hikes?

For while there once seemed to be a clearly inverse relationship between commodity prices and the dollar, these days we are more likely to see the dollar and commodity prices rise or fall together. Why is this and what are the implications?

A recent article by the BIS puts the change down to one, or both, of two factors. A temporary reason could be that the surge in energy prices caused by the war in Ukraine has also led to dollar strength as geopolitical and economic concerns have risen in tandem and lifted the dollar given its safe-haven attributes.

But as the conflict has worn on, so market sensitivity has eased, commodity prices have fallen back and the dollar has slipped. There could also be a longer-term structural issue as well which is that the US has become a net energy exporter and hence the dollar is acting more like any commodity currency that has a positive correlation with commodity prices.

The BIS article looks at the impact, this might have on commodity importers and exporters. For instance, commodity importers facing a rise in commodity prices no longer see the inflationary impact of this offset in part by dollar weakness. In addition, any dollar rally creates a tightening of financial conditions.

In short, a positive correlation between the dollar and commodity prices can create much more hardship for commodity importers when commodity prices rise. The flipside, of course is that commodity importers are better off if commodity prices fall and the dollar falls as well. This is because the disinflationary effects of lower commodity prices are compounded by both local currency strength against the dollar and the easing of financial conditions that come via a weaker dollar. Quite clearly, this is a very broad generalisation of the situation and, as already pointed out, this might just be a temporary change in the correlation anyway.

In addition, there might be other issues at play, such as the fact that there has been a very modest move away from pricing commodities in dollars, although we might expect this to weaken any correlation between the dollar and commodity prices, not necessarily turn a negative correlation into a positive one. The question we have is whether such a change in correlation – if it persists – alters the outlook for the dollar.

>> How will the US dollar move following the banking crisis?

Of course, this presupposes that, if there is any causation, and not just correlation, in this relationship it runs from commodity prices to the dollar, and not the other way around. This is debatable as we could argue that dollar strength creates tighter global financial conditions, weaker growth, lower commodity demand and hence lower prices (and the opposite when the dollar falls). And what the absence of a negative correlation these days may mean is simply that the dollar’s dominance in determining the global financial cycle has waned. But what if we ignore this and assume that any causation does run from commodity prices to the dollar?

If that’s the case, the dollar’s outlook depends on whether we think commodity prices will rise or fall. Energy prices will probably be of most importance in the commodity space given that the US has been a net exporter of gas since 2017 and of oil since late 2019. While we’re no commodity price forecasters, we suspect that based on this factor alone the dollar is perhaps more likely to rise than fall.

However, the causation, if any, probably does run more from the dollar to commodity prices, and not vice versa because of the dollar’s dominant role in determining the global financial cycle. The dollar could be losing some importance here, it might be the case that the relationship between commodities and the dollar is just becoming more random and not the strict inversion that we had seen prior to the past couple of years.