Has the US racked up too much debt?

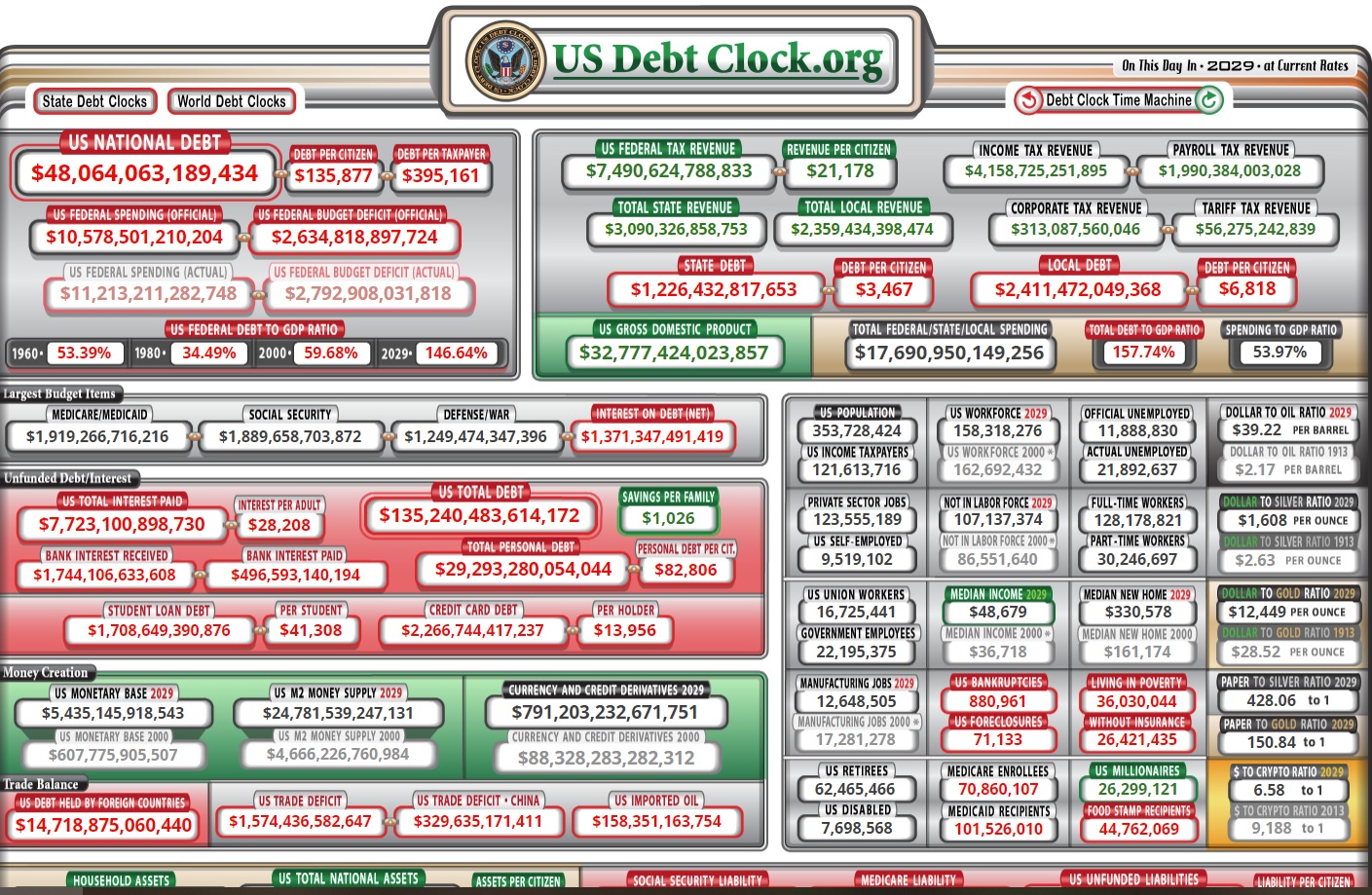

US Federal debt owned by the public has risen to just about equal the nation’s GDP having been only around a third of GDP just before the 2008 financial crisis.

Many analysts do not regard a 100% debt/GDP ratio in the US as particularly worrisome.

Estimates from the Committee for a Responsible Budget before the election suggested that incoming president Trump could add another USD8tr to the debt pile, for a rise of some 30% over the next decade. Almost a quarter of this debt is held overseas. All this leads to the question, has the US racked up too much debt, or could it do so in the near future?

What’s too much debt? It’s not an easy question to answer. We might argue that a debt ratio of around 100% is not high when we consider some countries have much higher debt, like Japan at well over 200% of GDP, or that many countries, such as the UK, have racked up much higher debt ratios during wartime. But is the debt/GDP ratio the right way to measure the ‘too much debt’ question?

This measure relates to the government’s supposed ability to pay down the debt and can certainly be onerous if the government has issued debt in another currency or one that it cannot print (as Greece found out between 2010 and 2012). But for governments with little, or no, foreign currency debt and a hand on the printing press, it can be argued that no level of debt is unaffordable even if paying it down with printed money has adverse consequences. Many analysts do not regard a 100% debt/GDP ratio in the US as particularly worrisome.

Steven Barrow, Head of Standard Bank G10 Strategy said one reason is that the “effective” debt burden may be lower than this because the US’s ability to pay down debt is better than its peers given the US’s central role in global finance, meaning the safe-asset role of treasuries and the dominance of the dollar. One study suggests that this dominance gives the US an effective debt cushion of some 22% of GDP. Simply put, a 100% debt/GDP ratio for the US is far less onerous than one of a similar size for any other country.

“If the debt/GDP ratio is not a worthwhile metric, what is? One thought is not to question the ability of the debtor to pay down the debt, but the willingness of the creditor (the bond market) to keep extending the finance. In theory, at least, it seems that creditors, particularly international ones, have an insatiable appetite for US debt on account of its safe-asset status”, said Steven Barrow.

In fact, there’s an argument that the US is almost forced to run large budget and current account deficits in order to effectively supply all the ‘safe assets’ that the world wants. But the logical conclusion to this would seem to be what’s called the modern day Triffin dilemma because, in supplying all these safe dollars the US racks up so much international debt that foreign creditors ultimately question the country’s creditworthiness, prompting capitulation in bonds and the US dollar. Not everyone believes this story and, at around 80% of GDP, it’s not clear that the US’s external debt-to-GDP ratio is burdensome at the moment.

What’s more, there’s an interesting angle here pursued by some of those sympathetic to Trump that the US’s real problem is not that it racks up too much debt, but that overseas investors want to put too much money in US assets. If that’s correct then the right policy is not to reduce the debt but to dissuade overseas investors from buying US assets. How can this be done?

In Steven Barrow’s view, by tariffs, blocking FDI into the US, undermining the Fed, using the US dollar as a weapon against ‘enemies’ like Russia, and favouring a weak-dollar policy; all policies that we’ve seen under Trump (and some under Biden for that matter). Of course, we don’t know that foreign investors want ‘too many’ US assets but the rising US dollar seems to be telling us that they are not satiated yet.