How strong is the U.S economy?

After two consecutive falls in 1H22, the U.S GDP is now back to the levels it was at the end of 2021.

The productivity in the US did recover by 0.1% in Q3 but fell a huge 3.8% in Q2 and an even bigger 6% in Q1.

Fed Chair Powell said that the US economy is “very strong” in his post-meeting press conference last week. But he also pointed out that the economy has shown no growth at all so far in 2022! Unless Powell has a very low bar when defining a ‘strong’ economy, something seems awry.

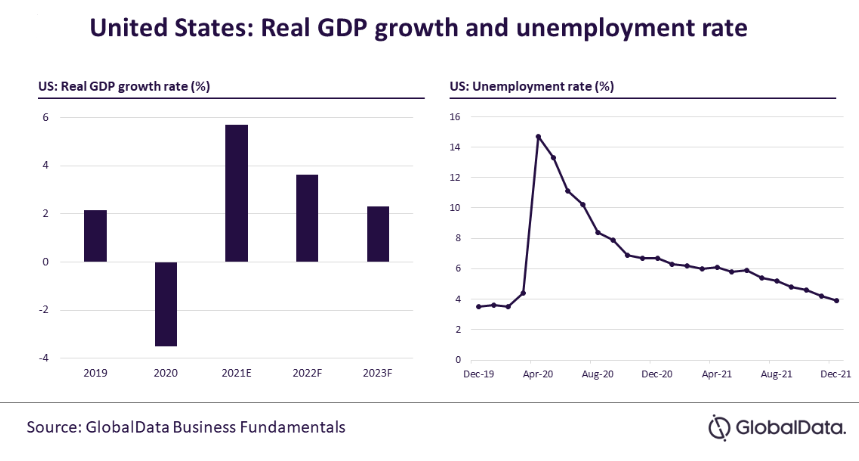

Powell was right to say that the economy has not grown this year. For while GDP did rise in Q3, after two consecutive falls in the first two quarters of the year, GDP is now only back to the levels it was at the end of 2021. The two-quarter fall in GDP in the first half of the year would be defined as a recession in most countries. The US only differs in the sense that it uses a private firm, the National Association of Business Economists (NBER), to officially declare a recession and, so far, they’ve chosen not to do that.

There had been excuses for the weakness such as the fact that the most commonly used expenditure definition of GDP understated other measures, such as the income measure. But recent revisions have largely closed this gap – and not in a way that provides any confidence that the economy is stronger than the expenditure data makes out. All told the economy – as defined by the best measure, which is GDP – is weak. It is not strong as Powell claimed.

What is strong is the labour market. Normally, strength in the labour market means strength in the economy. After all, if more people were employed, you would expect them to spend more (the expenditure definition of GDP), earn more (the income definition), and produce more (the output definition).

But what’s happened is that productivity has collapsed this year at a pace not seen since the data were first calculated in 1947. Productivity did recover by 0.1% in Q3 but fell a huge 3.8% in Q2 and an even bigger 6% in Q1. If more people are employed but they are, on average, producing less, GDP might not rise. And that’s what’s happened so far this year. There are lots of theories put forward for the collapse in productivity. These include a proclivity to hoard labour given the tight labour market, which means lots of workers becoming idle as demand in the economy slows.

Another is that investment and innovation have been weak as firms have focussed on struggling through the pandemic. Workers themselves might have become burnt out and less willing to put in effort given the difficult conditions for many during the pandemic and the decline in real wages. Only time will give us a better sense of whether the tumble in productivity is a temporary symptom of the pandemic, or a more structural factor that can also be related to the debilitating impact of the pandemic, among other things.

>> Will the US economy enjoy a soft or hard landing?

If there is no meaningful recovery in productivity, it is likely to mean that inflation will stay elevated as firms’ costs will stay high and they will try to pass these on in higher prices. In addition, employment could eventually start to fall quite sharply, should firms perceive that demand weakness will be sustained and don’t want to retain “unproductive” workers. This uncertainty over productivity adds yet another difficulty for the Fed and, indeed, many other central banks that are witnessing a similar bout of productivity weakness.

Mr. Steve Barrow, Head of Standard Bank G10 Strategy, said our sense is that the decline is mostly transitory, but also contains some longer-term structural aspects as well. As long as it persists, and stops strong employment growth from translating into robust GDP growth, it is wrong to describe the US economy as being “very strong”. If Fed Chair Powell and other FOMC members really believe that the economy is genuinely strong, then there has to be a greater danger that the bank tightens monetary policy too much. But as Powell has said many times; it is better to do too much (monetary tightening) than not enough.