How will OBBB impact the US dollar?

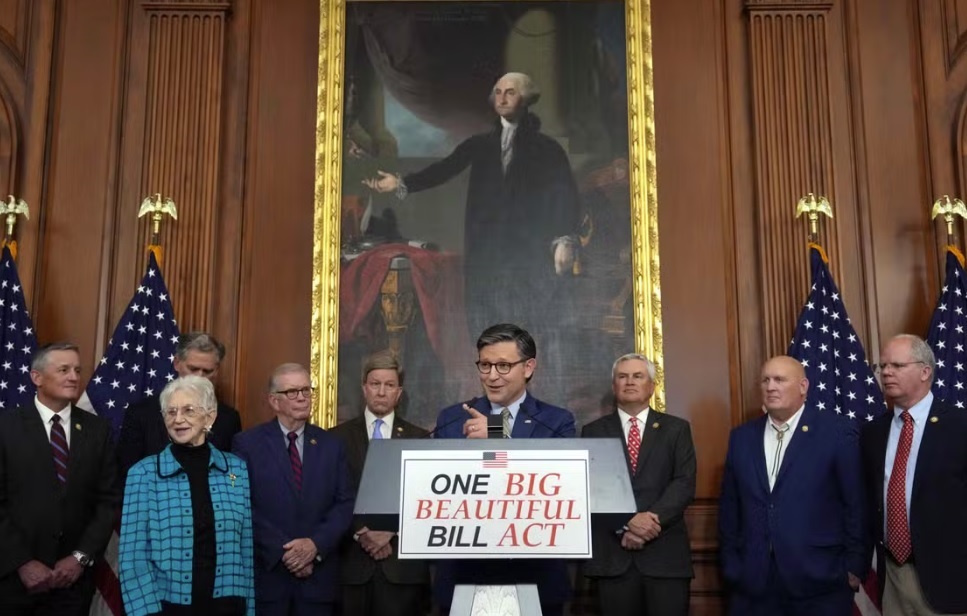

If the one big, beautiful bill (OBBB) gets through, it won’t really be cutting taxes at all and that could be important when it comes to the fate of the US dollar.

There are two senses in which the proposed tax cut is not a tax cut. The first relates to how it will impact the eeconomy, and the second relates to the way some Republicans want to account for the tax cut [sic] when it comes to the budget. To start with the first of these, the key point about the personal tax cuts, which the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) says will lift debt by USD3.8tr over the coming decade, is that they are not new cuts, but instead bring a permanence to the temporary tax cuts that Trump introduced in 2017. These cuts are due to expire at the end of 2025.

By making them permanent – at a huge cost – the tax cuts won’t necessarily stimulate the economy because most individuals won’t notice any difference. Only if individuals have made savings in the past to plan for the tax increase at the start of 2026 might we see some sort of stimulus as these savings can be spent once the tax cut becomes permanent. However, Steven Barrow, Head of Standard Bank G10 Strategy, said this would be extremely unlikely for two main reasons.

The first is that people don’t usually save up in advance to cushion the impact of a future tax hike. The second is that the US has a history of making temporary tax cuts permanent and hence we dare say that most individuals would have never seen the need to increase savings in the first place. This neatly brings us onto the other reason why – in some people’s eyes – this USD3.8tr tax cut should not be seen as a tax cut at all.

These ‘people’ sit on the Republican side in Congress and seemingly argue that because temporary tax cuts are usually made permanent the OBBB does not really include any tax cuts at all, save for new measures announced by President Trump, such as eliminating taxes on tips. To suggest that the US debt pile won’t increase by USD3.8tr over the next decade because the tax cuts are not really tax cuts may seem crass but, in an economic sense is perfectly correct given what we said earlier about the tax ‘cuts’ being unlikely to stimulate the economy.

But what does any of this have to do with the US dollar? Ordinarily, we might expect large tax cuts to lift a currency when an economy is around the full employment level – as the US is right now. Why? Because the central bank will presumably be concerned that tax cuts will stimulate the economy and, given full employment, lead to higher inflation. In response to this policy rates may rise and this lifts the currency.

For instance, big personal tax cuts by President Reagan in the early 1980s forced rates up – and lifted the US dollar significantly. But coming back to today, the tax cuts are unlikely to be stimulative for the reasons already explained. So rather than a policy combination of loose fiscal policy and tight monetary policy, which usually lifts the currency, the future seems to be one of loose fiscal policy and rate cuts. In our view, this is most definitely not the sort of policy combination that is likely to generate currency strength.

What’s more, the theory goes that looser fiscal policy and Fed rate hikes might lift the US dollar (as they did in the early 1980s) but only provide a temporary fillip because the market soon starts to worry about the funding of a much-increased budget deficit; especially if a good proportion of that deficit is financed externally. Again, this is what we saw in the 1980s as the US dollar strength generated by Reagan’s tax cuts and Fed rate hikes eventually gave way to significant weakness on twin deficit concerns (the budget and current account deficit).

Coming back to today, in Steven Barrow’s opinion, the risk is that the US dollar gets none of the initial lift from tax cuts (because the Fed does not hike rates) but all of the subsequent weakness as deficit concerns weigh on global investor sentiment.