Outlook for the US dollar in 2026

The US dollar's previous strength, which was predicated on "exceptionalism" in the US financial and economic markets, ended in 2025. Even while this kind of exceptionalism could come again, there are serious doubts about it strengthening the US dollar even more.

The US dollar's previous strength, which was predicated on "exceptionalism" in the US financial and economic markets, ended in 2025.

US dollar valuation

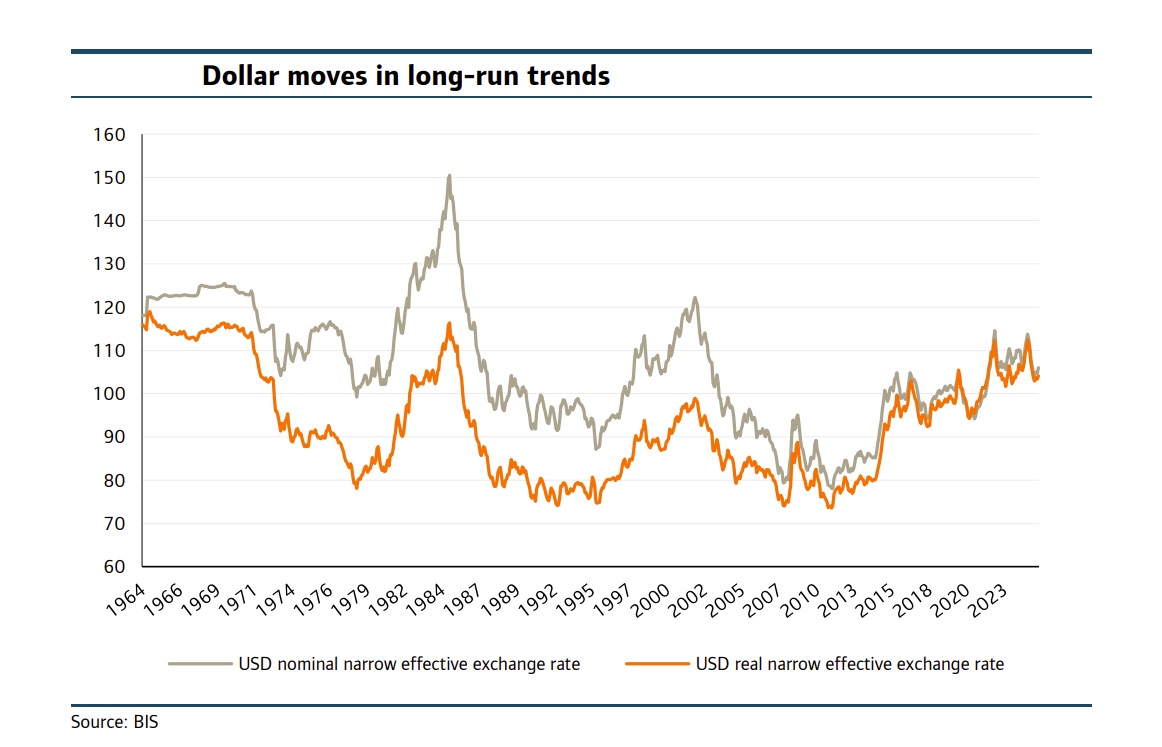

In this outlook for the US dollar, we focus on not just 2026 but subsequent years as well, and we are concerned primarily with the dollar’s overall level – meaning its effective exchange rate index – not its rate against a particular currency. The first place to start is to consider the US dollar’s valuation.

Now, we have to say straight from the off that we do not find measures of valuation, however defined, particularly useful for the dollar or other developed currencies. We see little reason why major currencies such as the US dollar should gravitate back to any sort of ‘equilibrium’ level over time. Many such valuation decisions are based on balance of payments considerations and, while these issues may have a role to play in emerging market countries with relatively modest currency trading, many analysts don’t believe that valuation is a useful concept for the dollar. But while the dollar might not naturally gravitate back to an equilibrium rate, Steven Barrow, Head of Standard Bank G10 Strategy sees two instances where valuation might matter. The first is when policymakers view a currency as inappropriately valued and make efforts, often through intervention, to pull it back. In the mid-1980s, for instance, the dollar became very overvalued, and policymakers intervened successfully to bring it back down.

The question now is whether the broad rise in the dollar for some years has left it at sufficiently overvalued levels that it could prompt action from the US. The answer seems to be ‘no’ on both counts. The dollar is not significantly overvalued, and the US authorities won’t do anything to try to weaken it. Of course, President Trump could return to the playbook we saw during his first term in office when he constantly bemoaned dollar strength, but it has not happened so far.

The second context in which valuation may matter does not actually relate to the ‘value’ of the dollar at all but, instead, to the valuation of other assets, specifically equities. The argument here is that if US equity valuations become overextended, leading to some sort of bubble burst, it will lead to a slump in the dollar as overseas investors either hedge any open-dollar exposures as they de-risk from US stocks, or sell outright, departing from both the equity market and the greenback. So, this scenario envisages that the dollar will slide if overvalued equities tumble. We did see this in the spring but, before that, the relationship between US stocks and the dollar was inverted as sliding stocks prompted heightened global risk aversion and a higher demand for safe assets such as the dollar. If this prior relationship returns, an overvalued US stock market might make us raise our expectations for the dollar, not lower them.

However, it is Steven Barrow’s view that this relationship has permanently altered, and hence, if US equity prices can be considered as overvalued (relative to any overvaluation in other stock markets), as perhaps seems to be the case, it should lead us to be more bearish about the dollar’s chances going forward. Steven Barrow’s broad conclusions, when it comes to the issue of valuation, are that the dollar is not sufficiently overvalued to think that the market will self-correct the dollar lower, or that policymakers will take effective means to lower the greenback. However, the relative overvaluation of US equities compared to peers, and hence the risk of a correction here, leaves us feeling that, on balance, valuation issues imply downside risk for the dollar.

The economic backdrop

The US economic ‘exceptionalism’ has seemingly bolstered the dollar for a number of years through helping to produce asset price exceptionalism, notably in equities. But this exceptionalism has narrowed considerably in 2025, possibly providing some impetus for the dollar’s fall.

2026 should see US growth outperform most other developed countries but there is an increasing bifurcation within the US that has earned the moniker, the ‘K’ shaped economy as AI-related investment soars while many other sectors struggle. There is also a growing ‘K’ shaped distribution to economic gains as higher-income deciles prove robust, while lower income deciles struggle.

The former appears aided by factors such as taxation policy and the wealth effects from the strong stock market. Evidence of weakness low down the income scale can be seen in indicators such as weak employment growth and rising loan delinquency. Which of these matters for the value of the dollar? Steven Barrow believes that it is the former; the supercharged AI-related investment, not the relative economic weakness elsewhere in the economy, provided this weakness is not sufficient to produce a recession that necessitates aggressive Fed easing.

In Steven Barrow’s view, the AI-related investment surge is key as this seems to be generating outsized productivity gains for the US relative to peers and, at the end of the day, if currencies are related at all to economic performance, it is more likely to be to productivity differentials than growth differentials. Here, it seems that, even if the US’s economic growth advantage over its peers in 2026 and beyond does not increase significantly from what we would have seen in 2025, a more robust productivity performance could still lift the dollar.

However, it is important to note that many aspects of US growth are being achieved in what might be described as dubious ways. Take tariffs, for instance. If US tariffs increase the US growth advantage over others, it will be because the US is essentially stealing growth from overseas. This is not just in terms of the tariffs themselves but also the pressure that has been put on other countries to make commitments to invest in the US in order to secure a lower tariff rate. The dollar’s slump in the spring of this year implies that the market is uncomfortable with these tactics.

A second ‘dubious’ method of achieving exceptionalism comes via the political pressure put on the Federal Reserve to deliver lower interest rates. For, if successful, this would also be a case of stealing growth, but this time from the future, as excessively low rates now would likely require excessively high rates in the future to keep increased inflation in check.

Thirdly, the widely agreed unsustainable debt path for the government might bolster US exceptionalism now, but clearly at the risk that bond vigilantes will reap their revenge at some point, as they seemingly tried to do back in the spring during Trump’s tariff tantrum.

Lastly, even the AI boom has some unsavoury aspects. These include the increasing use of non-bank financed debt to fund these enormous investment binges. We can also point to how rampant demand for power sources to build data centres, particularly electricity, potentially ‘steals’ access for others, if not through physical limits then at least through surging electricity prices. If we look at the last tech boom, the ‘dot.com boom of the mid-to-late 1990s’. However, while this trend was accompanied by surging tech stocks and a stronger dollar, the investment boom blew out as the Nasdaq crashed from March 2000, followed, not long after, by a slide in productivity and a long period of significant dollar weakness.

In short, those that might consider the dollar a buy, on the basis that the US will rebuild its exceptionalism, would have to factor in just how such exceptionalism is achieved. Is it fair and sustainable? Does it potentially undermine institutions such as the Fed? Does the rise in private and public debt lead to financial stability risks and, of course, are there bubble risks in the AI-related surge in equities? “In the short term, the momentum of the AI-related investment boom is likely to continue – and bolster US exceptionalism, and the dollar into the bargain. However, there will be risks associated with such dependence, and these seem likely to haul the dollar back in the longer term, as the dot.com boom and bust did for the dollar”, said Steven Barrow.

US Dollar’s dominance

The US faces rising government debt levels – as projected by the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO).

Rising government debt has been described by US politicians and policymakers as unsustainable, and creates risks to the dollar through the so-called ‘debasement’ channel mentioned earlier. However, the US has a number of ways to potentially navigate itself out of this problem that do not require fiscal austerity such as tax hikes or spending cuts. One is that the US can essentially grow its way out of debt, and it is clearly hoped, and perhaps expected by some, that an AI-fuelled growth surge will achieve this.

Another, more unique way, is to use dollar dominance by taking the lead in crypto; specifically, stablecoins. President Trump and others in the Administration believe that stablecoins can help cement dollar dominance at a time when the dollar’s position has come into question. There’s no doubt that the dollar dominates the stablecoin arena as virtually all stablecoins are pegged to the dollar. No doubt more non-dollar stablecoins will come along – but Steven Barrow suspects that the dollar will remain very dominant.

Many other authorities will likely prioritise central bank digital currencies over stablecoins and, as such, it is not clear to us that they will be geared to raising the profile of their currencies in the same way as we are likely to see in the US. But just as stablecoins could solidify dollar dominance and perhaps contribute to dollar strength, there are also risks.

Should some stablecoins lose their peg to the dollar, even temporarily, it could undermine confidence in the industry. This might be expected to apply to only the smaller and ‘riskier’ stablecoins, but even Tether’s XDT, which is dominant, faces question marks over the quality of ‘safe’ assets that support the 1:1 linkage with the dollar.

For instance, ratings agency S&P recently downgraded Tether’s stablecoin rating to “weak”, which is its lowest rating, partly due to the risker assets that make up its reserves. Clearly things may change here, and the US has put in place legislation to try to avoid any mishaps. But questions remain concerning the ability of stablecoins to promulgate dollar dominance – and hence we are wary at this stage of suggesting that they provide a route to dollar strength over the long haul.

Outside of the stablecoin arena, it seems that dollar dominance may be waning. Much focus is usually placed on the reserve allocation of central banks, which generally shows a move away from the dollar, albeit mostly to gold rather than other currencies. But in other areas too, the dollar’s dominance seems to be waning. International lending for instance has been stalled in dollars for some years, compared to many other.

In summary, the dollar is clearly still the dominant global currency by some distance. But this role is being challenged, both by many of the less savoury aspects of US policy such as tariffs, sanctions, political pressure on the Fed, and more, as well as efforts by others, notably China, to increase the allure of their currencies. The US fightback is coming through stablecoins – but it is not clear at this stage if this will breathe new life into dollar dominance – or represent a ball and chain around the dollar’s ankles.

If we run through the five sub-categories again, we’d argue that the first, valuation, is not likely to be of importance. Of course, President Trump could return to the dollarbashing we saw during his first term but we sense that his focus is on getting yields down, not the dollar. When it comes to the economic backdrop, Steven Barrow believes that the US will outperform most others in terms of growth. But the manner of any such exceptionalism troubles us.

For instance, tariffs might steal growth from others but, if the cost of this is distrust in US policymakers, then any such exceptionalism may not benefit the dollar at all, as back in 2025. As far as fiscal and monetary policy is concerned, it is not necessarily that interest rate differentials will more modestly against the dollar in 2026.

Instead, Steven Barrow feels that the market fears that the Fed will play fast and loose with inflation, just as the US government is playing fast and loose with debt. Both raise concerns about currency debasement and hence are negative factors for the dollar. 2026 is unlikely to see the dollar lose a significant amount of global dominance, but it will likely be whittled away very slowly. And while the rise of stablecoins could claw some dominance back, it may do so in a way that’s inherently risky for the dollar should stablecoins not be perceived as sufficiently stable.