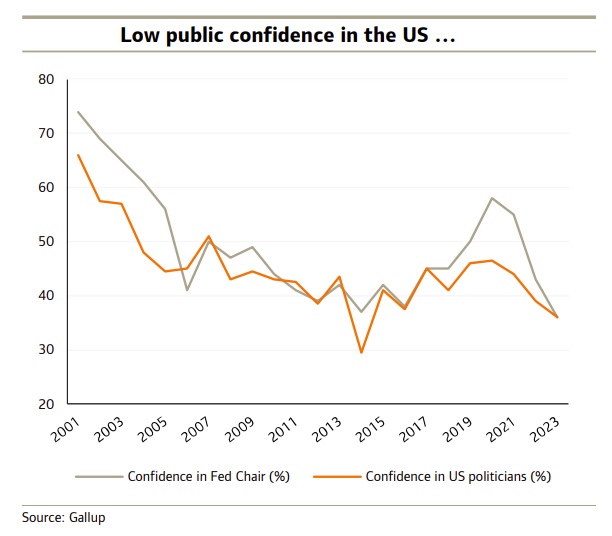

Trust in some central banks is declining

Trust in the Fed Chair is the lowest it has ever been according to Gallup and if you think that this is only a problem in the US, just look at the UK where politicians become steadily less trustworthy.

Trust in the Fed Chair is the lowest it has ever been according to Gallup

>> What to expect from Central Banks’ monetary policy?

We were interested to read recent research from the Chicago Fed that put some meat on the bones of a view that we’ve had for some time which is that we are all too pessimistic. The Chicago Fed research puts this “persistent pessimism” down to the effects of the pandemic but we think it might run a bit deeper than this.

The gist of the Chicago Fed paper is that the US economy has performed far better than surveys from consumers and businesses would lead us to expect. Consumers and small businesses have seen their confidence knocked by the pandemic. More specifically, the researchers at the Chicago Fed suggest that consumers and small businesses have not put as much emphasis on the strength of the labour market as before. It is a point that we – and others – have made before when describing why there has been a big discrepancy between the weakness of the University of Michigan consumer sentiment in the US and the robustness of the Conference Board’s measure.

For amongst other things, a difference in labour market treatment is a key factor in the discrepancy. But if, as the Chicago Fed researchers suggest, the turmoil created by the pandemic is the main reason for this pessimism, we might expect things to normalise as the pandemic continues to fade in the rear-view mirror – or can we? For it is here that we take a slightly different view. For while we totally agree that the pandemic has increased uncertainty and hit confidence, we see the source of this malaise as a bit more deep-seated and hence potentially longer-lasting. A clue to this comes in the decline of public confidence in policymakers; both those in government and in central banks. This confidence has undoubtedly fallen since the pandemic, but only as part of a long history of declining confidence.

For instance, back in the 1960’s more than seven in ten Americans ‘trusted’ that the US government of the day was doing the right things most of the time. Today, this proportion is down to just 16% and even in 2019, before the pandemic, it was around this sort of level. Trust in the Fed Chair is the lowest it has ever been according to Gallup and if you think that this is only a problem in the US, just look at the UK where politicians become steadily less trustworthy, while a net balance of 14% believe that the Bank of England is doing a bad job compared to a positive balance of close to 50% who thought that the Bank was doing a good job twenty years ago. This seems a widespread trend across countries and it would not be surprising if it were contributing to this sense of persistent pessimism.

>> Prospects for central banks’ monetary policy

Importantly, it might be creating pessimism even if the economic situation does not warrant it, as reflected in the currently low levels of unemployment, for instance. But why are policymakers considered so less trustworthy than they have been in the past?

The Standard Bank said it would be because the challenges they face are harder, like the pandemic. But, as we’ve seen in the case of wars, periods of extreme national fear are just as likely, if not more likely, to make leaders appear more trustworthy, not less. It wonders whether the era of greater communication, particularly social media has created a more toxic attitude towards policymakers and, not just this, but greater awareness and sensitivity to the more destructive – and arguably pessimistic – events that we see around the world.

In short, we may have to get used to a world in which the relationship between consumer/business sentiment and hard economic data are somewhat divorced. This could mean less emphasis on things like PMI surveys or consumer confidence measures, and more focus on hard data. And, as a last point, if financial market investors are part of this persistent pessimism as well, might asset prices generally perform better than most of these investors expect?