Which currencies will benefit from the US dollar’s retreat?

If we can agree that the US – the global financial hegemon – is in retreat and that the US dollar will fall, who will be the primary beneficiaries?

Will it be those that might seek to capture some of this US dominance, such as other ‘safe asset’ candidates like the yen and Swiss franc? Might it be those whose economic size could allow their currencies to capture some of the US dollar’s dominant share, such as the euro or the renminbi? Or might it be that there are actually no winners and losers? That the US dollar will decline in a pretty uniform fashion and we might actually see minor developed currencies and even emerging market currencies gain the most?

Whether it is actually happening or not, there seems little doubt that the overwhelming narrative in the FX market is that the US is losing, or likely to lose, some of its financial dominance and that this will bring with it a decline in the US dollar’s value. The US Administration’s aggressive tariff policy and its weaponization of the US dollar against adversaries are just two of the reasons why the market seems to be taking this view. But there’s been less attention paid to which currencies might have the most to gain from such a scenario.

On first blush it seems that those currencies that can challenge ‘king’ dollar through their economic size (China’s renminbi), or the depth of their financial markets (the euro zone’s euro) will be the winners. Or perhaps those currencies that act as a safe asset but don’t necessarily have economic clout or large financial markets, like the Swiss franc. If that’s the case we might expect these currencies to rise against other developed currencies as well as those in emerging markets. But Steven Barrow, Head of Standard Bank G10 Strategy, said there would be two problems with this view.

The first is that it is not clear to us that increased currency dominance brings currency strength. This is something we have discussed before. The second point, that we want to discuss today, is whether any other currency is ready and able to assume the US dollar’s mantle, or even take a small chunk out of the US dollar’s dominance.

We say this because there is an argument that the current situation may not be unlike the 1930s and 40s as the world transitioned from decades of sterling supremacy to one of US dollar dominance. And what was notable back then was that, in many people’s eyes, the US dollar was not ready to take over from the pound.

In fact, there was a name for it – the Kindleberger gap – after the famous economist Charles Kindleberger. That this period was associated with huge economic turmoil in the shape of the Great Depression and then World War Two, could prove an ominous sign when we consider the current economic outlook. But that’s not what we want to talk about here.

Instead, we want to note that the likes of the euro and renminbi are still some considerable distance from being able to fill the shoes of the US dollar; a Kindleberger gap may exist again today. The eurozone lacks key elements needed for a serious challenge to the US dollar. These include a fully formed banking , savings and investment and a single bond market amongst others.

Moreover, the eurozone has been tortuously slow in making any progress in these areas. ECB President Lagarde says that now is the chance for the euro to steal some of the dollar’s thunder, but that won’t happen until these things are fixed, and that could still take decades. China can move much more quickly when it wants to but clearly lacks the open capital markets to get any sort of renminbi challenge off the ground. This is not to say that the renminbi and euro can’t make tiny inroads into US dollar dominance, or that they will depreciate against the US dollar.

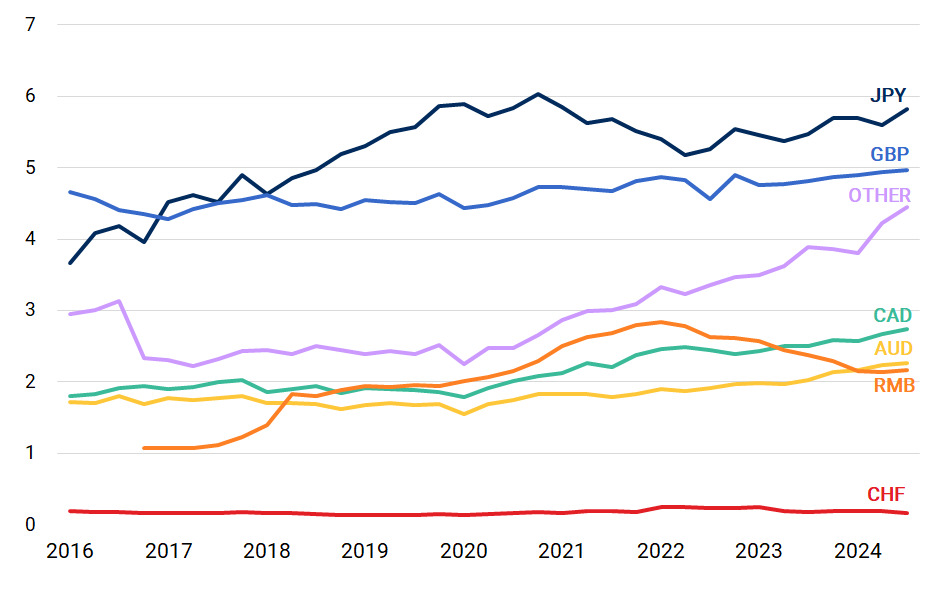

However, in Steven Barrow’s view, they won’t be ‘winners’ in the global currency stakes should the dollar continue to decline. Instead, we would see just as much strength, if not more, in currencies like the pound, the Australian dollar and even many emerging market currencies. And let’s not forget that there are many in the US administration that see dollar dominance as an exorbitant burden, not a privilege, given its implications, such as a huge trade deficit. So, for the eurozone and China it might be a case of – be careful what you wish for.