Will the US dollar see a sharp surge like in the 1980s?

The US dollar increased by almost 50% throughout the middle and late 1970s and 1980s. Will the past resurface?

If we take the beginning of the pandemic as the starting point the dollar is up only around 5% in effective terms

>> What are the prospects for major currencies?

It might be a very long time ago, but those searching for a period in history that most vividly mimics the situation today have had to go back to the mid-late 1970s and early 1980s. Surging inflation, massive central bank rate hikes and ballooning bond yields were all characteristics of that time – as they are today. But the mid-late 1970s and 1980s saw a near 50% rally in the US dollar and subsequent years saw an even bigger dollar decline. Are things different this time or could such a rollercoaster ride be on the cards?

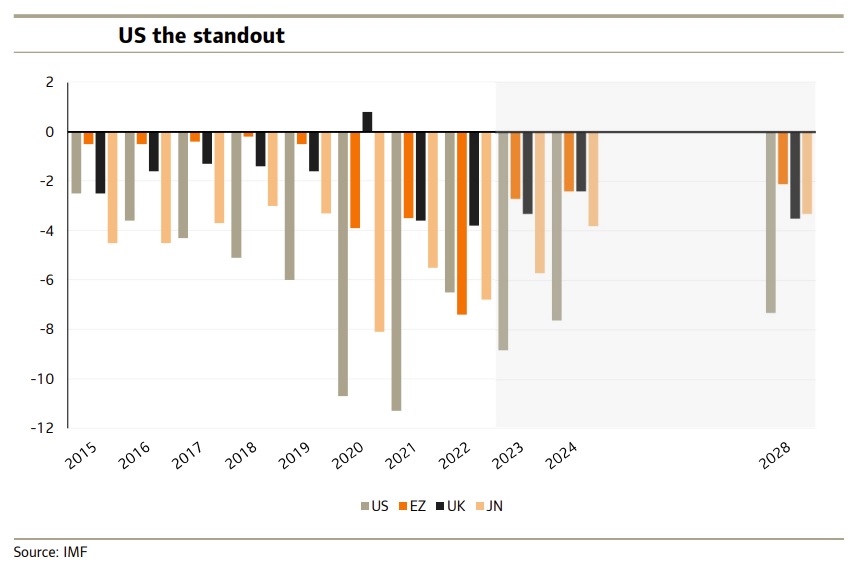

We say all of this because one thing that was notable from the IMF’s latest forecast which was released recently is that US fiscal conditions appear set to stay far more expansive than its developed-country peers. Back in the 1980s the dollar’s surge was put down, not just to rising policy rates from the Fed, but also very expansive – and largely unique – fiscal expansion from the Reagan administration.

The same loose fiscal/tight monetary policy combination seems to be in place right now and appears to be contributing to the surge in bond yields, just as we saw in the 1970s and 80s. The subsequent slump in the dollar from 1985 was undoubtedly helped by aggressive central bank intervention and that’s something that’s absent today; unless you look at the BoJ’s recent actions in the yen.

However, intervention was probably not the only story back then because the collapse in the dollar from 1985 was so dramatic. At the time, blame was put on the fact that the US’s rather unique budgetary position relative to other developed countries sucked in imports as well as foreign savings with the consequent surge in the US’s current account deficit weighing heavily on the dollar.

All of this might be very interesting, but does it act as any sort of template for what we might have seen recently and, most importantly, what we could see in the future? In theory, at least, it seems not, for we have already seen a surge in the US budget deficit, massive Fed tightening and, more recently, a surge in treasury yields and yet, despite all this the dollar has hardly risen.

If we take the beginning of the pandemic as the starting point the dollar is up only around 5% in effective terms and not much more than 10% if we start from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine; these are far below the 50% we saw in the late 1970s and early 80s when US inflation, the budget deficit, Fed policy rates and treasury yields all surged. Perhaps part of the reason for this is that US fiscal easing to date, while more aggressive than most, has not been the anomaly it seemed to be back in the 80s.

>> How will the US dollar react to a soft landing in the US?

However, going forward, if the IMF is right that the US structural budget deficit will still be up in the 7% region of GDP come 2028, or around twice the level expected in the likes of the euro zone, UK and Japan, the argument could be made that this will keep US yields high compared to the others and so create much more support for the dollar.

On the flipside, while intervention to bring down the dollar seems very unlikely, save for Japan, the US current account has deteriorated and, in our view, could weaken much further as domestic savings are depleted, so forcing the government to attract more foreign savings to meet the deficit. But even if the US current account deficit stays high at around 3.3% of GDP, as it was in the mid-1980s, or deteriorates further, Mr. Steve Barrow, Head of Standard Bank G10 Strategy does think that the growth of global financial markets and hence deficit financing makes this a much less onerous burden on the US dollar than it seemed to be back in the 1980s.

“Once we put all these arguments together the conclusion, in our view, is that the similarities between today and the 1980s will remain confined to things like inflation, policy rates and bond yields and will not progress to the dollar. The greenback won’t surge dramatically as a result of the US’s out-of-kilter fiscal policy, but neither will it subsequently slump as the ‘bill’ for this fiscal largesse comes via a wider current account deficit”, said Mr. Steve Barrow.