How do interest rates impact currencies?

If interest rates have any bearing at all on currencies, it is in real (inflation-adjusted) terms, not nominal terms. So, the fact that the Fed looks as if it will cut rates while inflation is rising is not going to be a good look for the US dollar.

It is debatable whether interest rates have much bearing on currencies, at least when it comes to big-developed currencies. Sometimes the correlation seems strong and other times it does not; which really means that there’s no correlation at all. Nonetheless, it is a good story for the market which is clearly obsessed by central bank policy as we will see again this week when the Fed meets. The US has the highest policy rates in the G10 but, this year at least, the weakest currency, which attests to the fast that rates don’t always matter. So why has the US dollar gone down if rates are so high?

The first reason, as Steven Barrow, Head of Standard Bank G10 Strategy wants to note, is that rates are not a primary determinant of currencies all the time and this year there has been so much else going on, in terms of tariffs, in particular, that the market has not really focussed on rates.

The second reason is that these tariffs should lift US inflation and lower it elsewhere. So, while nominal US rates have stayed high, adding in inflation expectations has rather undermined the US’s yield advantage. This being said, actual inflation in the US has not risen as much as expected so far and hence inflation expectations do not seem to have risen materially. The Fed, for one, still seems to think that they are anchored, although the likes of uber-dove Waller have chosen to ignore high-flying consumer inflation expectations and, instead focussed on low-flying market-based price expectations.

For instance, the 5-year forward starting 5-year inflation swap is around 2.5% which is about where it started the year and around the average we’ve seen for a few years now. This shows that the market is not fretting that higher inflation will become ingrained in the long-term once the tariff effect has washed out. Uber-dove Waller has emphasised that the tariff-effect on inflation is a one-off price rise that will fall away and the market seems to believe him. In sum, all this suggests that, as well as seemingly having a negligible role in what’s happened to the dollar this year, real US rates have not really fallen very much because inflation expectations have not increased materially.

But that, hopefully, explains what’s happened. What is to come could be very different. For one, tariffs will soon be old news and the market might, indeed, focus on other things – like real rates. Secondly, actual inflation seems certain to rise. The Bloomberg survey of US analysts suggests that PCE prices will rise 2.4% in Q2, 2.9% in Q3 and 3.1% in Q4. The key here is whether inflation rises more than most anticipate; Steven Barrow suspects it will and this will likely lift inflation expectations, perhaps even over the long haul.

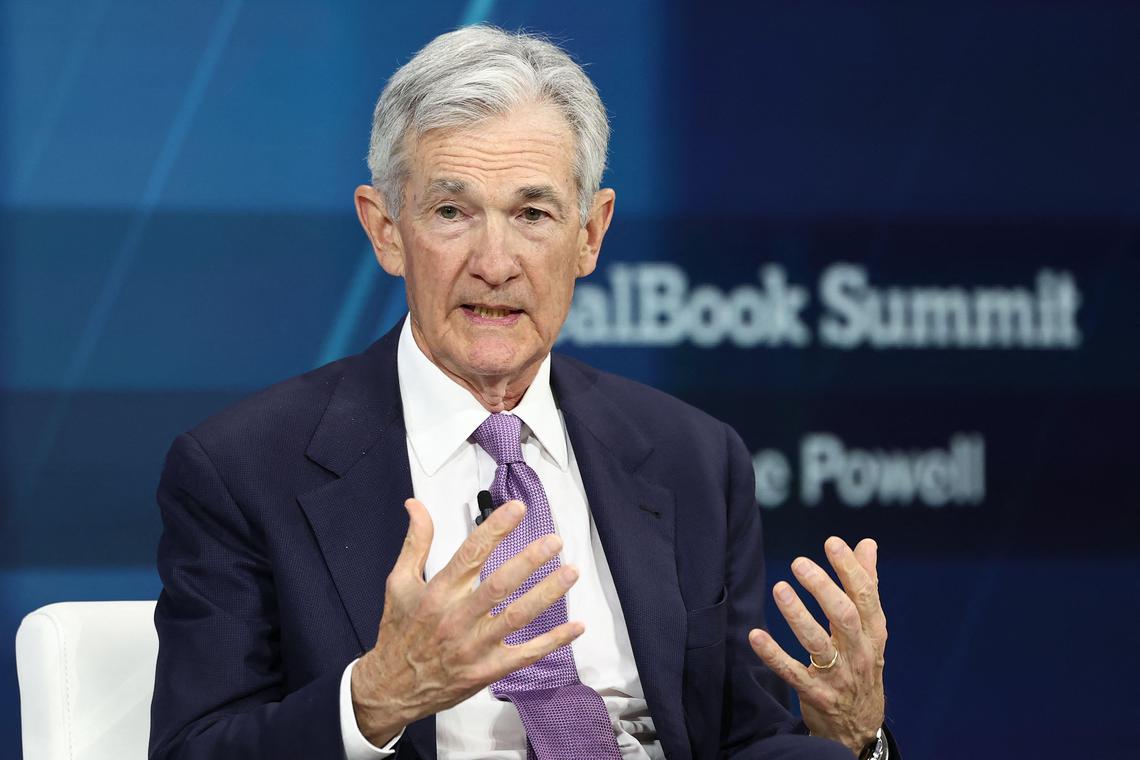

In short, the pressure on the US dollar from lower real US rates could intensify. But wait, we haven’t even got to the best bit yet, which is that the Fed is likely to be cutting rates. The market is pricing cuts to start from September with around five 25-bps cuts in all by the end of 2026 Most, or even all of these will likely take place against rising inflation.

History shows it is very rare for the Fed to be cutting rates into a bout of rising inflation. Usually cuts occur because economic weakness makes the Bank miss its full-employment target, and that’s normally an environment that brings with it lower inflation as well. One of the few times that the Fed cut as inflation was rising was in 2007. Whether these cuts were justified or not, the combination of Fed cuts and rising inflation was associated with a steep fall in the US dollar, right the way through to the time when the global financial crisis kicked in with Lehman’s demise in September 2008.

“Now, we are not saying that another financial crisis is around the corner. All we would point out is that Fed cuts and inflation increases don’t seem to make good bedfellows, either for the US dollar or for financial markets more generally”, said Steven Barrow.